INTRODUCTION

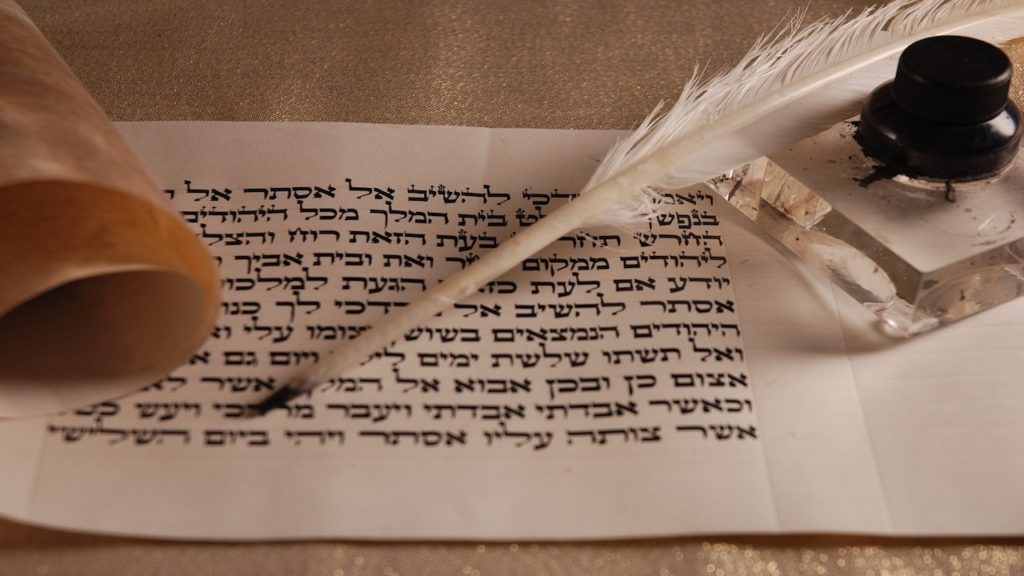

For centuries, it has been thought that classical humanism’s effect on Christianity was a negative one.[1] Renaissance humanism was thought to be largely secular in its nature; creating such a high view of man that the only natural result would be a diminished view of God. However, more modern research has uncovered much religious thought among the humanists of the Renaissance.[2] What used to be thought of as a hindrance to the healthy growth of Christianity, humanism is now seen as a contributor of some of the key ideas and philosophies that shaped Renaissance Christianity for the better; one of those ideas being ad fontes. Ad fontes is a Latin term meaning “to the sources.” In the context of Renaissance humanism and its application to Christian studies, ad fontes meant returning to the original manuscripts of Scripture to derive orthodox doctrine. Up until the Renaissance, the vast majority of Bible teaching was based off of Latin translations of the biblical text, not the original Greek and Hebrew it was written in.

Taking an immediate look at the era, it is easy to understand why such an approach to biblical study was needed: the Roman Catholic Church and her false teachings were in full swing. Opposition to the Church and its doctrines was increasing and its opposers needed a more stable foundation to base their protests on than faulty Latin translations. The majority of Scriptural interpretation at the time relied heavily upon allegory and anagogical methods. Because of increasing nominalism—a philosophy that rejected the abstract—a fresh, literal interpretation of Scripture is what was being demanded by the people.[3] This demand, along with the prevalence of humanistic education, allowed the idea of ad fontes to take root in Christian study, and provided the urging that Christian Renaissance scholars needed to return to the original manuscripts. Thus, ad fontes and classical humanism played an incredibly vital role in the shaping of Christianity during the Renaissance.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF AD FONTES

Peter Waldo and the Waldensians

To get an accurate grasp of the effect of ad fontes on Renaissance Christianity, we need to delve further back into the annals of history and try to decipher when the birth of this idea took place. We first have this idea presented by the Waldensians, a 12th Century group of French reformers who took their name from their most vocal and prominent member, Peter Waldo. Dissatisfied with certain doctrines and teachings of the Catholic Church, the Waldensians pled for and preached reform within the church. The Waldensians stood against papal authority, denied the existence of purgatory, and rejected the selling of indulgences, calling the pardons of the Pope a “cheat.”[4] But how is it that the Waldensians could be so opposing?

The Catholic Church during this time forbade lay people from being able to read the Bible for themselves, claiming that only the clergy of the church were given the special grace needed from God to be able to interpret Scripture correctly. Peter Waldo, of who very little detail of his life is known, either commissioned or was a large part of the translation of the Latin bible into the common tongue at the time, the Romaunt.[5] This allowed the Waldensians to be in possession of the first and only complete, literal, vernacular translation of the entire Bible that existed at the time,[6] therefore the Waldenses were able to compare the teachings of the Church to the teachings of Jesus and the apostles in the New Testament, see the obvious and blatant discrepancies, and begin to defy the teachings of the church, preaching to the public the new doctrines that they were discovering. The Waldensians angered the Roman Catholic Church because they were teaching to the lay people their own “literal” interpretations of Scripture. Of course, the Pope forbade them to teach these doctrines, but the Waldensians proclaimed that they must obey God rather than man and continued to publicly preach their doctrines.

The importance of having access to their own literal translation of the Bible proved invaluable to the plight of the Waldensians. Without this literal translation of the Bible, perhaps this beginning spark of reformation would never have ignited, and the fires of reform that burned in the hearts of men like Martin Luther and John Calvin would never have been enflamed. It is easily seen how this acts as a precursor to the idea of getting “back to the source” that inspired the Reformers of the Renaissance.

John Wycliffe and the Lollards

Later on in the 14th Century, we have John Wycliffe; most commonly nicknamed the “Morning Star of the Reformation.” Wycliffe was raised within the Catholic Church and received a very rigorous, one might say, humanistic, education, attending such institutions as Oxford, Baliol, and Merton.[7] He participated in ecclesiological politics and was an early opponent of the immense wealth and power of the clergy. This stance garnered him an unfavorable reputation with the medieval church early on and resulted in an issuance of five Papal Bulls against Wycliffe, denouncing his beliefs on divine and civil dominion. Although this did not stop Wycliffe from participating in ecclesiological debate, he instead turned his attention towards matters of theological doctrine. Stacey notes that Wycliffe’s mind began to turn to the central theological doctrines of the Church, and he published opinions, later deemed heretical, concerning the Eucharist, bringing down upon himself the wrath of the friars. He continued to denounce the evils of the Church and did not shrink from the theological consequences of his diatribes. He became Wyclif the heretic.[8]

Thus Wycliffe became a voice no longer of clerical change, but of complete ecclesiological reform. Wycliffe believed that the best way to bring about this reform was to get the bible into the hands of layman so that the church at large could see for themselves the egregious errors of the Church. Wycliffe took the matter into his own hands and completed a translation of the Latin Vulgate into the vernacular English. The availability of Scriptures for the common man coupled with Wycliffe’s preaching led to the formation of a group of reformers called the Lollards.

The Waldensians and the Lollards shared not only a mutual desire for reform in the church, but also a mutual source from which that desire sprang from: a deep conviction for personal, literal bible-teaching and reading. Both groups shared a desire to return to orthodox New Testament practices; a longing to go back to the source of their faith. It is from these two movements that we find the earliest instances of the idea of ad fontes. Although there were others who dissented against the church and fought for reform, the main movements based on an idea of literal interpretation of Scripture revolved around these two figures.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF HUMANISM

Francesco Petrarch

We must now look at the history of humanism. The overwhelming consensus is that Francesco Petrarch, an Italian scholar and poet, is credited with being one of the first humanists, even sometimes called “the Father of Italian Humanism.”[9] Petrarch begrudgingly studied law at the behest of his father. During his studies, he developed a pessimistic view of the intellect of his predecessors during the preceding centuries, claiming that the writings and intellectual contributions of the centuries past were ignorant. This led to him coining the term “Dark Ages.”

While acting as an ambassador for Europe, he was able to travel quite frequently. During these travels, Petrarch was able to accumulate many ancient Latin manuscripts and upon their inspection he developed a love for Latin literature. Unimpressed with the knowledge of the “dark ages” and captivated by the ancient works of Latin literature, Petrarch reached even further back and found intellectual satisfaction in the writings and culture of the Greeks and Romans. Petrarch found amongst these ancient writings that their authors harnessed immense power with their words. He reveled at the persuasiveness and eloquence of these early authors and used these works as a bridge to carry himself from being a skilled grammarian to becoming a capable rhetorician.[10] Petrarch’s influence spread vastly and greatly and it was his emphasis on the value of what he learned from the Greeks and Romans—the humanities, namely, grammar, rhetoric, and logic—that led Italian and European culture to embrace what came to be called a humanistic education.

Christian Humanism

One notable item pertaining to the rise of humanism is that a large majority of its earliest adopters were men of faith; and they did not view humanism as contradictory to any tenets of their faith. In fact, humanism in the Renaissance actually contributed much beneficial dialogue in regards to matters of Christian dogma. While it is true that the tendency of Christian Renaissance Humanistic thought was to lean towards an emphasis on humanity itself, it is wrong to think that this was done in a way that belittled the esteem that should have been offered toward God. One way that this can be seen is in the way that Petrarch described his view of himself in light of God’s holiness:

How many times I have pondered over my own misery and over death; with what floods of tears I have sought to wash away my stains so that I can scarce speak of it without weeping, yet hitherto all is in vain. God indeed is the best: I the worst. What proportion is there in such great contrariety? I know how far removed envy is from that best one, and on the contrary I know how tightly iniquity is bound to me. Moreover what does it matter that he is ready to benefit when I am unworthy to be treated well? I confess the mercy of God is infinite, but I profess that I am not fit for it, and as much as it is greater, so much narrower, indeed, is my mind, filled with vices. Nothing is impossible to God; in me there is total impossibility of rising, buried as I am in such a great heap of sins.[11]

Here it is seen that the emphasis placed on humanity during Renaissance studies served more to humble the Christian view of man, rather than to exemplify it. It is also of note to point out in the above quote the sheer eloquence with which Petrarch described his inner turmoil. This level of rhetorical skill was one of the main goals of Renaissance humanists. And this type of description can only come from a heart that has suffered through much honest introspection. In other words, the anthropological focus of the Renaissance was a beneficial one.

THE PRODUCTS OF CHRISTIAN RENAISSANCE HUMANISM

Erasmus

The foundation for the Reformation was already set: the Waldensians and the Lollards created the perfect environment for want of change and a desire to return to the “source” of their faith; Petrarch and the rise of humanism created the perfect vehicle to bring about that change. Christian humanism during the Renaissance taught that “if one could discover the real sources of Western Christian civilization—the Bible, the church fathers, the classics—one could purify Christianity of its medieval accretions and corruptions, thus restoring it to its pristine form.”[12] Enter Erasmus. Erasmus was well-known during his day as an intellectual giant. His wits, charm, and intelligence earned him favor and a good reputation with many of the leaders of the State as well as the Church. Erasmus took full advantage of the religious and scholastic climate prepared for him by the Waldensian, Lollard, and humanism movements and put all of his energy in “to one purpose—the revival of Christianity by means of a humanistic program, at once intellectual and ethical.”[13] The idea of ad fontes played a crucial role in Erasmus’ plan to revitalize Christianity, expressed clearly in his belief that “the way to correct the immediate past was to return to the remote past, to the world of the classics, the Bible, and the early church fathers.”[14] History shows us that Erasmus, continuing the rally cry started by Peter Waldo and John Wycliffe, and joined in his pursuits by the likes of Martin Luther, John Calvin, and Ulrich Zwingli, was successful in carrying out his mission of reform within the church. Without ad fontes and without humanism, such men would not have been formed and the Reformation would probably have not taken place.

The Puritans

But perhaps one of the greatest products to arise from humanistic and reformational thought was the Puritans. The successful Reformation wrought out by the reformers allowed for an environment free of ecclesiological politics, and the rise of Christian humanism allowed for a sharp, well-rounded growth of the mind. The combination of these two freedoms resulted in some of the greatest Christian thinkers the world has seen since the early New Testament church. Without having to pursue reform and armed with fresh, new, literal translations of the Bible, the Puritans were free to apply all of their energy to a passionate pursuit of the things of God, devoting the entirety of their mind, body, and soul to the serving of God. What stemmed from them were some of the greatest treatises and spiritual works that Christendom had seen since the early church fathers.

CONCLUSION

It is hard to imagine what the state of Christendom, or more so, the world, would be if the same fire that burned within these great Renaissance men burned also in the hearts of Christians today. It is even harder to imagine the change that would take place if we were all suddenly consumed with the same passion as the great Puritan preachers produced by this movement. The grandeur of this imagining is too great. However, the same difficulty is faced when pondering the potential fate of a 21st Century church that has not been shaped by the Renaissance, the Reformation, and the Great Awakening. The difference between these two visions is tantamount to the same contrast that Petrarch realized existed between his depravity and God’s holiness. What if Peter Waldo had never translated the Bible into the Romaunt? What if Wycliffe had never become “Wyclife the heretic?” What would have happened if Petrarch actually enjoyed the culture of the Dark Ages and felt content in devoting his studies likewise? All of the grim outlooks that these hypotheticals create testify to the great debt that we owe to classical humanism and the idea behind it that most impacted our faith: ad fontes.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bouwsma, William J. “The Spirituality of Renaissance Humanism.” In Christian Spirituality: High Middle Ages and Reformation, edited by Jill Raitt, 236-251. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1987.

Major, J. Russell. The Age of Renaissance and Reformation. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1970.

Stacey, John. John Wyclif and Reform. Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1964.

Thompson, Bard. Humanists and Reformers: A History of the Renaissance and Reformation. Cambridge: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1996.

Tracy, James D. “Ad Fontes: The Humanist Understanding of Scripture as Nourishment for the Soul.” In Christian Spirituality: High Middle Ages and Reformation, edited by Jill Raitt, 252-267. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1987.

Wylie, J.A. History of the Waldenses. Mountain View, CA: Pacific Press Publishing Association, 1977.

ENDNOTES

[1]I refer to this philosophy as “classical” humanism in order to distinguish it from “modern” humanism. Classical humanism as understood during the Renaissance was solely a philosophy of education. A “classical humanist” was simply one who studied the humanities. This is not to be confused with the modern-day usage of the term as a philosophy of life, a modern humanist being one who elevates the value of a human being as of the most supreme worth. For the purposes of this paper, all further mentioning of the term “humanism” shall be meant to be understood as “classical humanism.”

[2]James D. Tracy, “Ad Fontes: The Humanist Understanding of Scripture as Nourishment for the Soul,” in Christian Spirituality: High Middle Ages and Reformation, ed. Jill Raitt (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1987), 252.

[3]J. Russell Major, The Age of the Renaissance and Reformation (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1970), 27.

[4]J.A. Wylie, History of the Waldenses (Mountain View, CA: Pacific Press Publishing Association, 1977), 17.

[5]Wylie, 18.

[6]Ibid.

[7]John Stacey, John Wyclif and Reform (Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1964), 8.

[8]Ibid., 11.

[9]Bard Thompson, Humanists and Reformers: A History of the Renaissance and Reformation (Cambridge: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1996), 5.

[10]William J. Bouwsma, “The Spirituality of Renaissance Humanism,” in Christian Spirituality: High Middle Ages and Reformation, ed. Jill Raitt (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1987), 237.

[11]Bouwsma, 241-2.

[12]Thompson, 333.

[13]Ibid.

[14]Ibid.